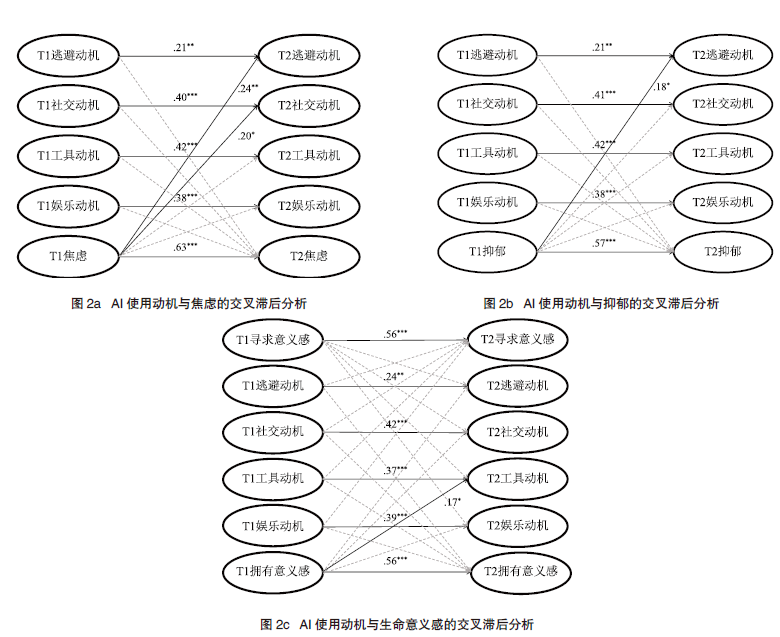

探讨大学生人工智能(AI)使用动机的异质性、影响因素及其与心理健康的关系。研究1于2024年9月对5760名大学生进行问卷调查。潜在剖面分析结果发现,大学生AI使用动机可划分为工具动机主导型(28.09%)、高工具-娱乐动机型(30.57%)、中等多元动机型(36.02%)、全面高动机型(5.31%)四种亚类型。不同亚类型在心理健康指标上的表现也显著不同。研究2于2024年9月与2025年3月对221名大学生进行为期半年的追踪研究,探究AI使用动机与心理健康之间的双向关系。结果仅发现心理健康对AI使用动机的短期效应,表现为焦虑情绪增加AI使用中的逃避动机和社交动机,抑郁情绪增加逃避动机,而拥有意义感可预测工具动机。研究结果揭示了大学生AI使用动机的群体异质性及其与心理健康的关系模式,为个性化干预和心理健康促进提供实证依据。

Abstract

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, an increasing number of university students are integrating AI into their academic studies and daily life. Based on literature review, the present empirical research examining the heterogeneity of motivations for AI use and its causal relationship with mental health is relatively limited, resulting in an inadequate understanding of the “empowering” potentials and “risk” concerns associated with AI use among university students. Moreover, existing research on the relationship between AI use motivations and psychological health is scarce, predominantly cross-sectional, and largely focused on negative indicators, restricting a comprehensive understanding of their mutual relationship. According to the dual-factor model of mental health, it is crucial to consider both positive and negative psychological health indicators when evaluating the association of AI use motivations and mental health, providing a more comprehensive and objective reflection of individual psychological well-being. Therefore, this study examines the relationship between four types of AI use motivations and mental health among university students by selecting flourishing and meaning in life as positive psychological indicators, and anxiety and depression as negative psychological indicators, to better understand the “empowering” and “risk” roles of AI use among university students.

This study used both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs to investigate the heterogeneity and influencing factors of university students’ motivations for AI use and their relationships with mental health. Study 1 was a cross-sectional survey of 5,760 university students from cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Zhengzhou, and other cities in China. All participants completed a questionnaire regarding university students’ AI use and mental health. Latent profile analysis identified four subtypes of AI use motivations: the tool-oriented type (28.09%), the high tool-entertainment motivation type (30.57%), the moderate multi-motivation type (36.02%), and the globally high motivation type (5.31%). Gender, grades, place of birth, and major effectively predicted these subtypes of AI use motivations among university students. Moreover, significant differences in mental health levels were observed among the identified latent classes of AI use motivations, with the efficiency high tool-entertainment motivation group scoring the highest, followed sequentially by the tool-oriented, moderate multi-motivation, and globally high motivation groups, which scored the lowest.

In Study 2, 221 university students from a university in Henan Province were selected to participate in a six-month longitudinal survey exploring the bidirectional relationship between AI use motivations and mental health. Cross-lagged analysis indicated that anxiety significantly predicted escapism motivation and social motivation, depression significantly predicted escapism motivation, and a higher sense of meaning significantly predicted instrumental motivation, while AI use motivation did not significantly predict mental health indicators.

The findings reveal the heterogeneity of university students’ motivations for using AI and their relationship with mental health. These results provide empirical evidence for personalized interventions and psychological health promotion strategies. However, there are some limitations need further consideration. First, the longitudinal survey included only two waves of data collection over a six-month interval, with a relatively small and homogeneous sample. Future research could increase the number of survey waves (e.g., three or more), expand the sample size, and enhance sample heterogeneity to more comprehensively and accurately reveal the long-term relationship patterns between AI use motivations and mental health. Second, the survey in this study was conducted from 2024 to 2025, at which time the overall intensity of university students’ motivations for AI usage was not yet prominent. With the rapid popularization and deeper integration of generative AI technologies among university students, the intensity and structure of motivations for AI use within this group may change. Therefore, future research should continuously observe and dynamically track the evolving trends of university students’ AI use motivations, capturing their actual conditions and patterns of change more accurately in the current context.

关键词

人工智能使用动机 /

心理健康 /

大学生 /

潜在剖面分析 /

交叉滞后效应分析

Key words

artificial intelligence use motivation /

mental health /

university students /

latent profile analysis /

cross-lagged panel analysis

{{custom_sec.title}}

{{custom_sec.title}}

{{custom_sec.content}}

参考文献

[1] 蔡芬, 贾枭, 沈文钦. (2025). 生成式人工智能在我国研究生学术写作中的应用现状及其影响.中国高教研究, 1, 75-82.

[2] 方俊燕, 温忠麟, 黄国敏. (2023). 纵向关系的探究:基于交叉滞后结构的追踪模型. 心理科学, 46(3), 734-741.

[3] 龚栩, 谢熹瑶, 徐蕊, 罗跃嘉. (2010). 抑郁-焦虑-压力量表简体中文版(DASS-21)在中国大学生中的测试报告. 中国临床心理学杂志, 18(4), 443-446.

[4] 蒋舒阳, 刘儒德, 冯毛, 洪伟, 金芳凯. (2024). 自尊与中学生问题性手机使用:社交焦虑和逃避动机的中介作用. 心理科学, 47(4), 940-946.

[5] 赖巧珍. (2017). 大学生心盛状况及其在心理健康双因素模型中的应用研究(硕士学位论文). 南方医科大学,广州.

[6] 李艳, 许洁, 贾程媛, 翟雪松. (2024). 大学生生成式人工智能应用现状与思考——基于浙江大学的调查. 开放教育研究, 30(1), 89-98.

[7] 李艳, 朱雨萌, 孙丹, 许洁, 翟雪松. (2025). 典型科研场景下生成式人工智能使用的差异性分析——学科背景与人工智能素养的影响. 现代远程教育研究, 37(2), 92-101+112.

[8] 罗力群. (2021). 对自然科学和社会科学的比较:研究对象、逻辑推理和理论发展. 社会科学论坛, 5, 161-178.

[9] 王鑫强. (2013). 生命意义感量表中文修订版在中学生群体中的信效度.中国临床心理学杂志, 21(10), 720-729.

[10] 王鑫强, 谢倩, 张大均, 刘明矾. (2016). 心理健康双因素模型在大学生及其心理素质中的有效性研究. 心理科学, 39(6), 1296-1301.

[11] 谢爱磊. (2016). 精英高校中的农村籍学生——社会流动与生存心态的转变.教育研究, 37(11), 74-81.

[12] 尹奎, 彭坚, 张君. (2020). 潜在剖面分析在组织行为领域中的应用.心理科学进展, 28(7), 1056-1070.

[13] 原晋霞, 朱晋曦, 王希, 柏宏权. (2022). 我国东部发达地区学前儿童使用人工智能产品的现状、差异及机制研究——基于家长视角的调查. 电化教育研究, 43(10), 33-40.

[14] 周浩, 龙立荣. (2004). 共同方法偏差的统计检验与控制方法.心理科学进展, 12(6), 942-950.

[15] Abbas, M., Jam, F.A. & Khan, T.I. (2024). Is it harmful or helpful? Examining the causes and consequences of generative AI usage among university students. International Journal of Education and Technology in High Education, 21, 1-22.

[16] Armutat S., Wattenberg M., & Mauritz N. (2024). Artificial Intelligence: Gender-specific differences in perception, understanding, and training interest. Proceedings of the International Conference on Gender Research (ICGR), Barcelona.

[17] Blumler, J. G., & Katz, E. (1974). The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research. Sage Annual Reviews of Communication Research Volume III. Sage Punlication, Inc.

[18] Chan, C. K. Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Students' voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Education and Technology in High Education, 20, 43.

[19] Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464-504.

[20] Choi, T. R., & Drumwright, M. E. (2021). “OK, Google, why do I use you?” Motivations, post-consumption evaluations, and perceptions of voice AI assistants. Telematics and Informatics, 62, 101628.

[21] Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

[22] Diener E., Wirtz D., Tov W., Kim-Prieto C., Choi D., Oishi S., & Biswas-Diener R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143-156.

[23] Fulmer R., Joerin A., Gentile B., Lakerink L., & Rauws M. (2018). Using psychological artificial intelligence (Tess) to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 5(4), e64.

[24] Guo Y., Li Y., & Ito N. (2014). Exploring the predicted effect of social networking site use on perceived social capital and psychological well-being of Chinese international students in Japan. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(1), 52-58.

[25] Huang S., Lai X., Ke L., Li Y., Wang H., Zhao X., & Wang Y. (2024). AI technology panic- is AI Dependence bad for mental health? A cross-lagged panel model and the mediating roles of motivations for AI use among adolescents. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 1087-1102.

[26] Huo W., Li Q., Liang B., Wang Y., & Li X. (2025). When healthcare professionals use AI: Exploring work well-being through psychological needs satisfaction and job complexity. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 88.

[27] Jung, T. & Wickrama, A. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 302-317.

[28] Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351-354.

[29] Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 4(2), 207-222.

[30] Klimova, B., & Pikhart, M. (2025). Exploring the effects of artificial intelligence on student and academic well-being in higher education: A mini-review. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1498132.

[31] Korgaonkar, P. K., & Wolin, L. D. (1999). A multivariate analysis of Web usage. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(2), 53-68.

[32] Leung, L. (2007). Stressful life events, motives for Internet use, and social support among digital kids. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 10(2), 204-214.

[33] Linnea L., Andrea B., Michael G., Diana I., & Celeste C. C. (2024). Too human and not human enough: A grounded theory analysis of mental health harms from emotional dependence on the social chatbot Replika. New Media and Society, 26, 5923-5941.

[34] Master A., Meltzoff A. N., & Cheryan S.(2021).Gender stereotypes about interests start early and cause gender disparities in computer science and engineering.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,118(48), 1-7.

[35] Naragon-Gainey K., McMahon T. P., & Chacko T. P. (2017). The structure of common emotion regulation strategies: A meta-analytic examination. Psychological Bulletin, 143(4), 384-427.

[36] Ndung' u J., Vertinsky I., & Onyango J. (2023). The impact of social media use on the autonomy and organisational citizenship behaviour of faculty members in Kenyan private universities. Journal of Decision Systems, 32(4), 653-677.

[37] Ng, Y. L., & Lin, Z. (2022). Exploring conversation topics in conversational artificial intelligence-based social mediated communities of practice. Computers in Human Behavior, 134, 107326.

[38] Petrescu M. A., Pop E. L., & Mihoc T. D. (2023). Students' interest in knowledge acquisition in Artificial Intelligence. Procedia Computer Science, 225, 1028-1036.

[39] Portela C., Palomino P., Challco G., Sobrinho A., Cordeiro T., Mello R., & Isotani S. (2024). AI in education unplugged support equity between rural and urban areas in Brazil. I13th International Conference on Information & Communication Technologies and Development, Kenya.

[40] Qu Y., Tan M. X. Y., & Wang J. (2024). Disciplinary differences in undergraduate students' engagement with generative artificial intelligence. Smart Learning Environment,11, 51.

[41] Rodríguez-Ruiz, J., Marín-López, I. & Espejo-Siles, R.(2025). Is artificial intelligence use related to self-control, self-esteem and self-efficacy among university students?. Education and Information Technologies, 30(2), 2507-2524.

[42] Rosa A. C. D., Dacuma A. K. C., Ang C. A. B., Nudalo C. J. R., Cruz L. J., & Vallespin M. R. D. (2024). Assessing AI adoption: Investigating variances in AI utilization across student year levels in far eastern university-Manila, Philippines. International Journal of Current Science Research and Review, 7(5), 2699-2705.

[43] Rruplli E., Frydenberg M., Patterson A., & Mentzer K. (2024). Examining factors of student AI adoption through the value-based adoption model. Issues in Information Systems, 25(3), 218-230.

[44] Skjuve M., Brandtzaeg P. B., & Folstad A. (2024). Why do people use ChatGPT? Exploring user motivations for generative conversational AI. First Monday, 29(1), 1.

[45] Soomro K. A., Ansari M., Bughio I. A., & Nasrullah N. (2024). Examining gender and urban-rural divide in digital competence among university students. International Journal of Learning Technology, 19(3), 380-393.

[46] Wei X., An F., Liu C., Li K., Wu L., Ren L., & Liu X. (2023). Escaping negative moods and concentration problems play bridge roles in the symptom network of problematic smartphone use and depression. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 981136.

[47] Xie, T., & Pentina, I. (2022). Attachment theory as a framework to understand relationships with social Chatbots: A case study of Replika. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2022, Hawaii, USA.

[48] Yurt, E., & Kasarci, I. (2024). A questionnaire of artificial intelligence use motives: A contribution to investigating the connection between AI and motivation. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(2), 308-325.

[49] Zhang S., Zhao X., Zhou T., & Kim J. H. (2024). Do you have AI dependency? The roles of academic self-efficacy, academic stress, and performance expectations on problematic AI usage behavior. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 34.

[50] Zhao L., Liu Y., & Su Y. S. (2023). Personality traits' prediction of the digital skills divide between urban and rural college students: A Longitudinal and cross-sectional analysis of online learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educational Technology and Society, 26(4), 150-162.

基金

*本研究得到全国教育科学规划教育部青年项目(EEA240407)的资助

PDF(1436 KB)

PDF(1436 KB)

PDF(1436 KB)

PDF(1436 KB)

PDF(1436 KB)

PDF(1436 KB)